“Oh, another one from Google University,” he scoffed, flipping through my chart without making eye contact. I sat on the paper-covered table, knees bouncing, trying not to cry.

I’d waited four months for this referral. Four months of chest tightness, brain fog, and crushing fatigue no one could explain.

“I mean,” he said, turning to the nurse with a smirk, “if she spent less time diagnosing herself online and more time exercising, maybe she’d feel better.” My face burned with humiliation.

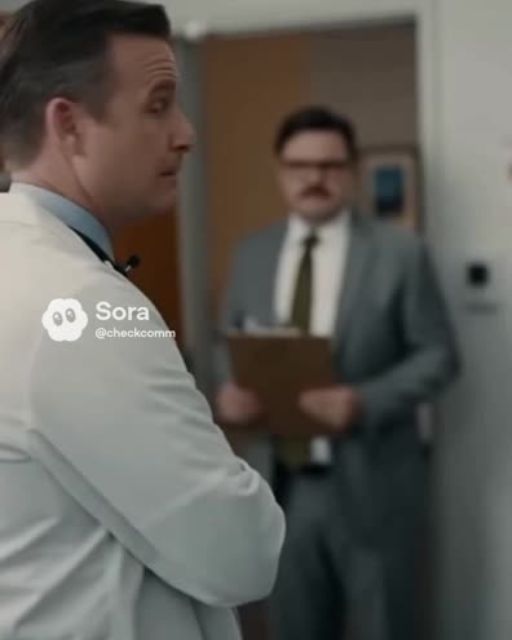

I opened my mouth to respond. Then the door clicked open behind him.

His face dropped instantly. “Dr. Mirani,” he stammered. “I didn’t realize you were—”

The woman behind him raised an eyebrow. “I could tell.” She was the lead consultant… and the doctor my GP had actually referred me to.

She walked past him like he was invisible. She took one look at me and said gently, “You’re not crazy. I’ve seen this before.”

She ordered bloodwork immediately. Imaging. Referrals.

And when the results came back, the “imaginary illness” had a name. And a treatment plan.

But the real shock came later: what Dr. Mirani said to the nurse in private—and how the nurse responded—ended up in his permanent record.

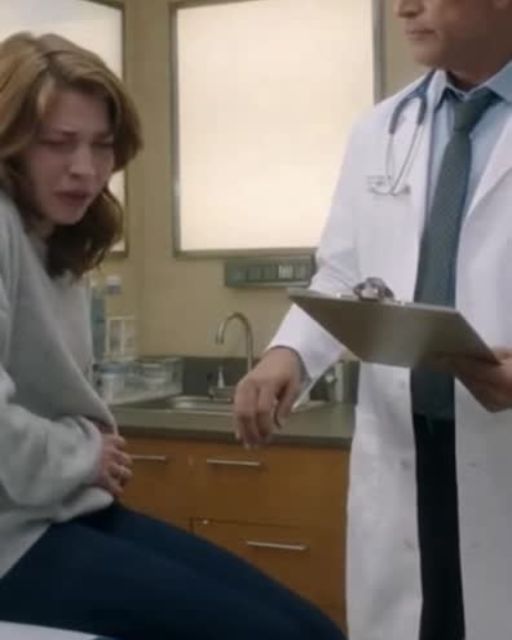

She didn’t address him immediately. Instead, she pulled the rolling stool closer and sat at my eye level.

“I’m sorry you were spoken to like that,” she said gently. “That’s not how we treat people here.”

My throat tightened, and I nodded because I knew if I spoke, I would cry. The nurse shifted uneasily.

I saw guilt in her eyes—the guilt of someone who’d heard this before and hadn’t always fought back. “Can you tell me your symptoms from the beginning?” Mirani asked. “Don’t rush. I have time.”

I had never heard a doctor say that. I started from the beginning—last winter, the flu that never quite went away, the sudden shortness of breath, the heavy fatigue.

I explained the chest pressure, like someone sitting on my ribs even when tests came back “normal.” I told her about the brain fog so thick it scared me.

I told her how I’d started setting alarms to remember to eat because my mind kept drifting. She listened without interrupting.

There were no eye rolls. No sighs.

When she asked questions, they were calm and precise. “Any fainting?” she asked. “Any rapid heartbeats when you stand up?”

“Yes,” I whispered. “Sometimes when I stand, my heart feels like it’s doing jumping jacks. They told me it was anxiety.”

She nodded and made careful notes. “And the fatigue—mornings or evenings?”

“Evenings,” I said. “But sometimes all day.”

She turned to the computer and started placing orders. “Full blood count. Autoimmune panel. Thyroid. Ferritin and B12.”

“Let’s add inflammatory markers, D-dimer, and a tilt table referral,” she murmured. “We’re going to look properly.”

“If everything’s normal, we keep looking,” she added. Behind her, the other doctor—Dr. Harris—clicked randomly through my chart.

“Is all that really necessary?” he muttered. “Her ECG is normal, her chest X-ray is clear, and she’s young.”

He said “young” like it was a diagnosis. Mirani didn’t even look at him.

“Yes,” she said. “Because she’s young and has disabling symptoms. That’s when we don’t brush people off.”

The nurse, Lena, pressed her lips together like she was trying not to smile. “I’ll print the blood forms,” she said and slipped out.

A few minutes later, I walked out with a stack of appointment slips. It still hurt that I’d been mocked, but for the first time, I felt hope.

As I walked down the hallway, my hands shook from everything that had just happened. That’s when I heard voices through the thin wall.

“Close the door, please,” Mirani said sharply. The soft click followed.

I shouldn’t have listened, but I did. I stood still, pretending to scroll my phone.

“What you said to that patient was unacceptable,” she said. “You are not to belittle patients or their sources of information.”

Harris sounded defensive. “She admitted she’d been looking things up online. They all do. It feeds their symptoms.”

“And mocking them helps?” she shot back. “You delayed her workup because you decided she was anxious.”

“She has documented shortness of breath, tachycardia, and collapse episodes,” she continued. “That warrants evaluation.”

“Her ECG is normal,” he insisted. “You saw it.”

“Myocarditis can show minimal ECG changes,” Mirani replied. “Autoimmune conditions wax and wane. POTS isn’t obvious unless you look.”

Then came the part that changed everything. “Lena,” she said. “I’m documenting this interaction. I need you to confirm what you heard.”

Silence followed. Then Lena spoke.

“When we walked in, he called her ‘another one from Google University,’” she said. “He implied she doesn’t exercise enough. He’s said similar things before.”

My lungs froze. She didn’t have to say any of that. She chose to.

“Thank you,” Mirani said. “This will be included in my report to the clinical lead and in his performance review. This is a pattern.”

Harris sputtered something inaudible. But the tone was unmistakable—shock.

A few days later, my phone rang early in the morning. I answered groggily.

“Hi, it’s Dr. Mirani,” she said. “Is now okay?”

My heart dropped. Doctors don’t call if everything is fine.

“Yes,” I said. “We got your results back,” she said. “Your inflammatory markers are high, and your cardiac MRI shows mild myocarditis.”

“Your autoimmune panel is suspicious too.” My world narrowed to her voice.

“So it’s real?” I whispered. “You’re not imagining this,” she said. “Your symptoms fit what we’re seeing.”

“We need to act early,” she added. “I want to admit you for monitoring.”

I felt tears fill my eyes. It was terrifying and validating all at once.

“Okay,” I breathed. “Okay.”

“You likely have an autoimmune component,” she said. “And this could have been missed for months if we assumed anxiety.”

That sentence hit me harder than the diagnosis. I was admitted that week.

The ward hummed with machines and quiet footsteps. Lena was on shift my second night.

“How are you holding up?” she asked. “Terrified,” I said. “But relieved too.”

“That’s normal,” she said. “Now you know what you’re dealing with.”

As she checked my vitals, she hesitated. “I’m glad you were there when she walked in,” she said softly.

“Me too,” I said. “Perfect timing.”

“No,” she said. “You weren’t the first patient he dismissed. We reported him, but nothing stuck.”

Then something shifted in her voice. “My sister died at thirty-two,” she said. “Doctors said it was anxiety.”

“It wasn’t,” she whispered. “It was autoimmune. They found it too late.”

My chest tightened. “I’m so sorry,” I said. “Thank you for standing up. For her. And for me.”

“If more of us had spoken sooner,” she said, “maybe things would’ve been different. So now I speak up.”

Treatment began the next day. Medication for inflammation. Monitoring. Too many wires.

Slowly, the fatigue lifted a little. My chest eased. My body started to trust itself again.

A few weeks after discharge, I got a letter from the hospital. It was an invitation.

They were reviewing patient communication standards. They wanted my feedback.

I went to the meeting with trembling hands. Two patients, a liaison, three doctors—including Mirani.

“I’m not a medical expert,” I said. “I just had Google and a body that didn’t feel right.”

“But mocking patients doesn’t help,” I continued. “It teaches us not to come back.”

A doctor with tired eyes nodded. “We forget that,” he said.

Afterward, Mirani pulled me aside. “There was a review,” she said. “Harris is on a performance plan.”

“His clinic is being audited. Your case was one of several.”

My stomach flipped. I hadn’t wanted to destroy someone’s life—just stop the harm.

“Does he know it was me?” I asked. “He knows it was his behavior,” she said.

Months passed. My life shifted into a new normal.

One day at the hospital for a follow-up MRI, I saw someone sitting alone near admissions. Slumped. Pale.

It was Harris. No white coat. Just a man with a hospital band on his wrist.

He looked up and recognition flickered across his face. Then something like shame.

I stepped closer. “Waiting for tests?” I asked softly. He nodded.

“Yeah. Cardiac stuff.” The irony almost knocked the breath out of me.

“It’s scary,” I said. “Waiting.” “It is,” he whispered.

For a moment, he wasn’t the doctor who mocked me. He was a patient terrified of bad news.

“I hope you get good answers,” I said. “And a good doctor.” He let out a shaky breath. “Me too.”

I walked away feeling something loosen inside me. Not forgiveness, but release.

My next follow-up with Mirani was calm. She showed me scans, pointing out improvements.

“You’re healing,” she said. “Slowly, but healing.” I nodded.

“Sometimes I still feel like I made it up,” I admitted. She shook her head gently.

“That’s normal after being dismissed,” she said. “But your results tell a clear story. Your body was asking for help.”

On my way out, I saw Lena again. “How’s the heart?” she asked. “Less angry,” I joked.

She laughed. “We like cooperative organs.” Then her expression softened.

“Your story is being talked about,” she said. “Not with your name. But in a necessary way.”

That night, I wrote everything down. Not as a complaint, but as a story.

I wrote about the months of being told it was anxiety. The jokes. The dismissal.

I wrote about the consultant who walked in at the perfect moment. About a nurse who refused to stay silent.

And about the twist—the doctor who mocked my Google searches sitting in the same waiting area, waiting for answers.

Not revenge. Just balance. Life has a way of making people face their own lessons.

If there’s a point to all of this, it’s not “don’t Google your symptoms.” It’s this: trust your body, even when others don’t.

You’re allowed to ask for another opinion. You’re allowed to insist on being heard.

And if someone laughs at your pain, walk away. Find the one who listens.

If this story resonates with you—even a little—share it. Like it. Send it to someone who keeps saying, “Maybe I’m overreacting.”

Because sometimes, the right story at the right time is the door that finally opens.