We hadn’t even started real training yet. Just the intake stuff—vaccines, paperwork, gear issue. I thought I was tough. Played rugby. Had a busted collarbone once. But standing there in boots two sizes too big, stomach growling, some dude sobbing while a sergeant screamed about “pee ghosts,” I felt my spine soften.

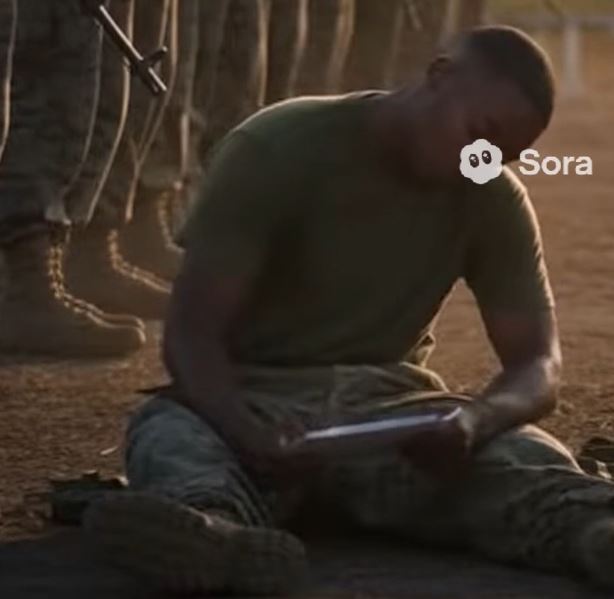

Week one, we lost three. One tapped out during rifle drills—just sat down in the dirt and said, “I’m done.” Another faked a seizure, didn’t even try to sell it. The third just vanished overnight. Like, literally packed up and ghosted. No one talked about him.

I kept going, mostly out of spite. My hands split open during the obstacle course—rope burns so deep I could see raw pink. We weren’t allowed to use ointment. “Let ‘em harden,” the corporal said, flicking ashes from his cigarette like it was holy water.

You learn to move without thinking. Eat without tasting. Sleep with one ear on full alert. We did push-ups in icy rain until my vision tunneled. I watched a guy pass out mid-squat and hit his chin so hard his teeth clicked like castanets.

But then came the day with the gas chamber.

We lined up. One by one, they shoved us in, masks off. My lungs seized instantly. Mucus poured out of my nose, and my eyes? Burning oil. People screamed. Someone tried to claw the door. And right in front of me—this quiet guy from Quebec named Liron—he just dropped.

Not passed out. Dropped like his body gave up.

I don’t even remember deciding to do it, but I grabbed his collar and yanked him up. He was coughing hard, stumbling. I pushed us both toward the door, yelling something—I couldn’t hear it over the alarms. A sergeant yanked us out and dumped us into the dirt like fish from a net.

Liron was out cold. They rushed him to med. I was told nothing. No pat on the back. No “good job, soldier.” Just: “Back in line, Nowak.”

That night, I couldn’t sleep. Not because of the gas. Because I saw something in myself I hadn’t expected. I wasn’t trying to be a hero. I just reacted. I didn’t know if Liron would even come back.

He did. Four days later, pale and quiet, but standing. He didn’t say much. Just gave me a folded note and walked away.

Inside, it said: “Didn’t think anyone would care. You proved me wrong. Merci.”

I still have it, tucked in an old watch box at home.

Week six came and the drills got brutal. We were crawling under barbed wire while live fire cracked overhead. My thighs were cut up, my shirt soaked through with blood and mud. Someone got their ear nicked. No one stopped.

One guy, Marten, kept messing up the cadence. He was tall, lanky, kind of clumsy. Each time he slipped, we all paid. More push-ups. More screaming. I hated him, honestly. It wasn’t personal, but in that heat, hate felt easy.

Then one night, I caught him sitting behind the mess hall, crying into his hands.

I almost walked away. But something pulled me toward him—maybe because I’d been that guy once.

He told me his wife was 32 weeks pregnant. That she’d begged him not to enlist, but they needed the benefits. He hadn’t told anyone. Said he was scared she’d go into labor and he wouldn’t be there. He looked up at me and said, “I thought this would make me a better man. But what if she needs me now?”

I didn’t know what to say. I just sat beside him. Didn’t offer advice. Just listened.

Next morning, I took the heat for his screw-up in PT. I didn’t say why. Just did the reps.

A week later, his wife did go into labor early. He got emergency leave. When he came back, he brought a photo of his baby girl, tucked in beside his ID tags. Named her Mira. Said it meant “peace” in Slavic.

That’s when I realized this place didn’t just test your body. It cracked open your soul, looked at what was inside, and decided whether it was worth forging.

By week eight, I had my first real injury. My ankle rolled during a night drill—stepped in a rabbit hole, full sprint. Felt like a lightning bolt shot up my leg. I tried to walk it off. Bad idea.

The medic said it was a “minor sprain” but it felt like someone had taken a hammer to my joint. I got crutches. No running for ten days.

I thought I was done. That they’d roll me back to a new platoon. But my squad—guys I barely knew eight weeks ago—they carried my gear for me. Even Marten. Especially Marten.

“I owe you one,” he said. “This is me paying interest.”

It shocked me how quickly strangers had become brothers.

The weirdest part was, once I stopped focusing on the pain, I started paying attention to people more. I noticed how Adil always hummed before a run—same off-key Arabic tune. How Jericho, the oldest guy in our group, tucked a photo of his daughter into his boot before every drill. Said it made him run faster.

And Liron—quiet, sharp-eyed Liron—turned out to be an artist. He’d sketch people at night in his notebook. One day, he showed me a drawing of me hauling him out of the gas chamber. He’d captured my expression so perfectly it gave me goosebumps.

“You looked angry,” he said. “Like you were mad I might die.”

That’s when I knew: I wanted to finish. Not for the uniform. Not for the glory. But because we’d all seen each other at our worst and still chose to keep going.

Then came the final field week. No bunks. No mess hall. Just seven days in the woods, cold rations, no sleep. It was meant to simulate combat—fog of war, surprise drills, the whole deal.

One night, it rained so hard our trench collapsed. Jericho’s foot got caught in the mud and he screamed. Loud. The drill sergeant was on us immediately, yelling to fix it.

And then I heard it—panic in Marten’s voice.

He was stuck too. But worse. The mud had pulled him in waist-deep and was sucking harder with every move. I grabbed a branch, tried to wedge it in, told him to hold on.

“I can’t—I can’t feel my legs!” he shouted.

Liron and Adil came running. No command. No orders. Just instinct. We formed a chain, hands locked, pulling Marten free like our lives depended on it.

It took twenty minutes. Felt like hours.

When we finally yanked him out, he collapsed on the grass, gasping. Jericho had managed to free himself, limping but okay. We were soaked, filthy, freezing—and laughing. Like absolute lunatics.

I’ll never forget that laugh. That was the moment I knew: we’d made it. Not officially, not yet. But spiritually. We were soldiers now.

Graduation came a week later. Families arrived. Cameras, hugs, stiff new uniforms. My mom cried. My dad slapped my shoulder and said, “Proud of you, son,” which from him was like a standing ovation.

But the best part? Liron handed me a second sketch. This one of our whole squad, standing in a field, faces worn but proud. At the top, he’d written in small, neat script: Steel is made in fire.

He handed it to me and said, “For when you forget who you are.”

I kept that one too.

Years later, when I was back home, walking through the market, a man stopped me. Said I looked familiar. Turned out, it was Marten’s brother. Said Marten had gone on to become a medic. Helped save lives in Syria. “Says you saved his first,” he told me.

I didn’t know what to say. Just nodded and smiled.

Here’s what I’ve learned: Basic didn’t make me a soldier. The people did. The breakdowns. The late-night talks. The moments no one saw.

It taught me that strength isn’t about being the toughest or the loudest. It’s about who you pull out of the mud when no one’s watching. It’s about standing in hell and still reaching for someone else’s hand.

So yeah, I thought basic would break me. But it didn’t. It built me—from the inside out.

If this hit you, or reminded you of someone who served—or someone still serving—share it. Tag them. Tell them you see them.

And if you’re the one struggling: someone out there will pull you out of the mud. You just have to hold on.