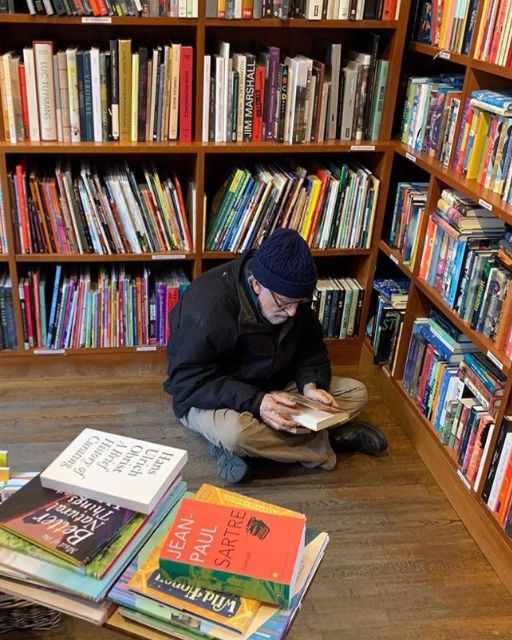

He came in right as we opened—quiet, bundled in a navy coat and beanie, like the chill had followed him in.

Didn’t say a word. Just nodded politely and made his way to the children’s section.

At first I thought he was browsing for grandkids, maybe waiting on someone. But he didn’t buy anything. He didn’t even stand.

He just sat there, cross-legged on the wooden floor, one book after another in his lap. “Where the Wild Things Are.” “Harold and the Purple Crayon.” “Goodnight Moon.” All the classics, all well-loved, like he’d known them by heart for years.

He didn’t look up, not even when I glanced over during my shift. It was as if he was in a world all his own, a world created by the pages of those books. He turned each one slowly, his hands weathered and gentle, and every so often, I could see him smile to himself as if he was remembering something precious.

This routine went on for a week. Every morning, right when the store opened, he would come in and sit on the floor, flipping through book after book. Not once did he make eye contact or speak. He was always alone. No one ever joined him.

The bookstore I worked at was a small, cozy place—old wooden shelves, the smell of ink and paper in the air, and the soft hum of conversation from a handful of regulars who would drift in and out. We had a few kids who came in with their parents, but this man was different. He seemed to exist outside of time, as though the world around him didn’t quite matter.

Curiosity gnawed at me, so one day, after he had finished reading “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” I couldn’t help but approach him. My feet carried me toward him before I could even stop myself.

“Excuse me,” I said, gently interrupting the silence that had become his company. “I’ve noticed you reading a lot of children’s books. Is there something special about them?”

He looked up at me, and for the first time, I saw the depth in his eyes—something worn, like someone who had lived through a storm and emerged with a quiet understanding of the world. He didn’t seem startled, just… thoughtful.

“I suppose I like the simplicity,” he said, his voice gravelly, as though it hadn’t been used in a while. “There’s something comforting about the way these stories always end well.”

I wasn’t sure what to say to that. I wanted to ask more, to understand the layers of this man, but I hesitated, unsure of how far to push. But the question that had been circling in my mind for days slipped out before I could stop it.

“Why do you sit here and read all day? Every day. Why not at home?”

His face softened, and his lips twitched as if he might laugh. But it wasn’t a laugh of amusement—it was one of recognition, of shared sorrow that didn’t need words.

“I used to read these stories to my daughter,” he said, his voice quieter now, his gaze distant as if he were seeing something far away. “She loved them. ‘Goodnight Moon’ was her favorite. Every night, we’d read it together before bed, her little head on my shoulder. She… she’s gone now.”

I didn’t know what to say. The air between us felt heavy, and I could see the pain behind his words. The weight of it was there, almost suffocating, but also grounding, like he had come to terms with something I couldn’t yet understand.

“Did she… was she sick?” I asked gently, not wanting to press, but unable to stop myself.

The man sighed, a deep exhale, and he nodded slowly.

“She was. Leukemia. It came on fast. One minute, she was running around playing, and the next, we were in the hospital, watching her fade away.”

He paused, and I noticed the way his hands gripped the pages of the book a little tighter, his fingers trembling ever so slightly.

“After she passed, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I couldn’t just go home, sit there, and feel empty. So I came here. I’d sit in the corner and remember the way she used to laugh when I’d read these books to her. I came to see if maybe… maybe if I read them enough, I could find a little piece of her again.”

My heart ached for him. The sadness in his eyes, the quiet devastation, was too much to bear. It was a pain that went beyond the loss of a child—it was the kind of grief that hollowed out a person, leaving behind only memories and the desperate hope that those memories might somehow fill the void left behind.

“I’m so sorry,” I whispered, my voice thick with emotion. “I can’t imagine what that must be like.”

He gave me a small, sad smile, one that didn’t quite reach his eyes, but there was something in it that showed he appreciated the empathy.

“I don’t think you need to imagine it,” he said, his voice soft but steady. “Everyone has their own kind of grief. We all lose something. Some of us lose more than others, but we all feel it. This… reading, it’s just my way of holding on to what I had. The books remind me of her.”

I nodded slowly, letting his words sink in. I didn’t have the right words to say, so I just stood there, silently offering him the space he needed. I had never seen grief like this up close before, and it was humbling in a way I couldn’t quite explain.

As the days passed, I began to notice that the man wasn’t just reading the books. He was memorizing them. I saw him reread the same lines over and over, muttering the words to himself like a mantra. He wasn’t just holding on to the memories of his daughter—he was trying to preserve them, to keep them alive within him.

One afternoon, after I had closed the shop and was tidying up, I found him sitting on the floor again, his coat draped over the back of the chair. His hands were resting on his lap, his gaze fixed on the wall. He looked… at peace, in a way I hadn’t seen before.

I approached him once again, this time more cautiously.

“You’ve been coming here for weeks now,” I said, not sure what to expect. “And I’ve been wondering… have you thought about telling your story? Maybe sharing it with others, like you’ve shared it with me?”

He turned his gaze toward me, and for the first time, I saw a flicker of something—hope, perhaps.

“I’ve thought about it,” he admitted. “But it’s not easy. Talking about her, it brings it all back. The pain, the guilt… I feel like I should have done more, should have found a way to save her.”

“Grief doesn’t have a timeline,” I said gently. “It’s okay to feel that way. But maybe by sharing your story, you could help others who feel like they’re alone in their grief, too. You’ve been holding onto these books and these memories for so long. Maybe it’s time to let others hold them with you.”

He considered my words for a long moment before he nodded slowly.

“You know… maybe you’re right. Maybe it’s time.”

A few weeks later, he returned to the bookstore, but this time, with a notebook in hand. He had started writing—his daughter’s story, his own, the pain, and the healing. And, eventually, he published it in a small online journal for parents who had lost children.

The feedback he received was overwhelming. Messages of support, of gratitude, from parents who had been through the same thing, or were struggling with their own pain. It was his way of turning his grief into something meaningful, and in doing so, he found a new sense of purpose.

But the real twist—the karmic twist—came when he started receiving donations for a charity he’d created in his daughter’s memory. The funds helped families with children undergoing treatment for leukemia, providing them with financial assistance for medical bills, transportation, and lodging.

Through sharing his pain, he found a way to help others, to give back in a way that his daughter’s memory could live on. And in the process, he began to heal.

Sometimes, the hardest stories are the ones we keep locked inside. But when we share them, when we let others in, we discover that we’re not alone. And in helping others, we often help ourselves.

If this story resonated with you, share it with someone who might need to hear it today. And remember: your story matters. Your pain matters. And you have the power to turn it into something beautiful.